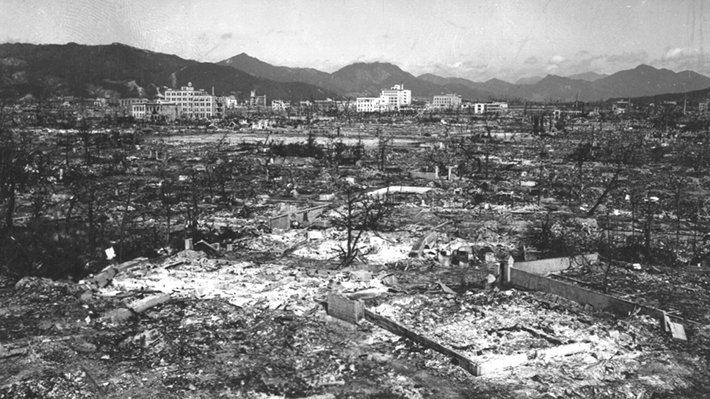

Seventy-seven years after the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, killing at least 110,000 and wounding hundreds of thousands more, two religious leaders—one Buddhist and one Catholic—share their views.

Yuki Miyamoto, a Hiroshima-born ethicist and professor of Religious Studies and Global Asian Studies at DePaul University, Chicago, is outraged that Western public opinion has largely exonerated the United States for its indiscriminate use of nuclear weapons as well as its continued testing and production of them after the bombing of Japan.

In a recent article, Miyamoto, whose mother narrowly survived the atomic attack, argues that while the devastation of the atomic bombs dropped on August 6 and August 9 on Hiroshima and Nagasaki appears to have been acknowledged, the U.S has failed to address the philosophical, religious and spiritual issues that continue to haunt survivors.

The views of religious leaders who lived in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the aftermath of the atomic attacks on those cities “offer insights into our violent world,” writes Miyamoto, who is the author of the 2012 book, Beyond the Mushroom Cloud: Commemoration, Religion, and Responsibility After Hiroshima.”

Miyamoto points out that hibakusha, as the survivors of the atomic attacks are called in Japanese, offer a valuable opportunity to “reconsider the ethics of responsibility in the atomic age.”

Hiroshima, the first target of the U.S. atomic attack on Japan, is renowned for Shin Buddhism, Japan’s largest Buddhist school, popularly referred to as the “True Pure Land school of Buddhism,” according to Miyamoto.

Kōji Shigenobu, a survivor of the atomic attack on Hiroshima who lost many family members and grew up to become a prominent exponent of Shin Buddhism, “developed a perspective on the bombing that represented many Hiroshima residents’ frame of mind,” says Miyamoto

“Kōji viewed the atomic bombing as representing three circles of sins: the sins of Hiroshima residents, of Japanese nationals and of humanity as a whole,” Miyamoto writes.

Hiroshima was the site of a major Japanese military base from which soldiers were sent to battlefields and occupied countries across Asia.

Although he condemned Japan’s military aggression that played a key role in the Second World War, Kōji also targeted Hiroshima residents whom he described as selfish for abandoning bombing victims. He also condemned Japan for its military aggression and lamented that humanity had become warmongers.

“Such human nature, according to Kōji, invited the atomic bombing,” says Miyamoto.

Kōji’s “critical self-reflection and attempts to go beyond a black-and-white understanding of good and evil…may offer an insightful perspective on how to escape cycles of violence,” writes Miyamoto.

Nagai Takashi, a Nagasaki physician who converted to Catholicism, offered a somber view of the U.S. atomic bomb attacks on Japan.

He likened the victims of the atomic bombings to “sacrificial lambs, chosen by God because of their unblemished nature.” And he said It was thanks to their sacrifice that the war came to an end.

_______________

From its beginnings, the Church of Scientology has recognized that freedom of religion is a fundamental human right. In a world where conflicts are often traceable to intolerance of others’ religious beliefs and practices, the Church has, for more than 50 years, made the preservation of religious liberty an overriding concern.

The Church publishes this blog to help create a better understanding of the freedom of religion and belief and provide news on religious freedom and issues affecting this freedom around the world.

The Founder of the Scientology religion is L. Ron Hubbard and Mr. David Miscavige is the religion’s ecclesiastical leader.

For more information visit the Scientology website or Scientology Network.